In the conclusion of my post analyzing NYC taxi and Uber trips, I noted that Citi Bike, New York City’s bike share system, also releases public data, totaling 22.2 million rides from July 2013 through November 2015. With the recent news that the Citi Bike system topped 10 million rides in 2015, making it one of the world’s largest bike shares, it seemed like an opportune time to investigate the publicly available data.

Much like with the taxi and Uber post, I’ve split the analysis into sections, covering visualization, the relationship between cyclist age, gender, and Google Maps time estimates, modeling the impact of the weather on Citi Bike ridership, and more:

- Visualization: One Day in the Life of the Citi Bike Share System

- The Data

- Age, Gender, and the Accuracy of Google Maps Cycling Time Estimates

- Anonymizing Data is Hard!

- Magical Transports

- Quantifying the Impact of the Weather on Citi Bike Activity

Code to download, process, and analyze the data is available on GitHub.

One Day in the Life of the Citi Bike Share System

I took Citi Bike trips from Wednesday, September 16, 2015, and created an animation using the Torque.js library from CartoDB, assuming that every trip followed the recommended cycling directions from Google Maps. There were a total of 51,179 trips that day, but I excluded trips that started and ended at the same station, leaving 47,969 trips in the visualization. Every blue dot on the map represents a single Citi Bike trip, and the small orange dots represent the 493 Citi Bike stations scattered throughout the city:

If you stare at the animation for a bit, you start to see some trends. My personal favorite spots to watch are the bridges that connect Brooklyn to Lower Manhattan. In the morning, beginning around 8 AM, you see a steady volume of bikes crossing from Brooklyn into Manhattan over the Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg bridges. In the middle of the day, the bridges are generally less busy, then starting around 5:30 PM, we see the blue dots streaming from Manhattan back into Brooklyn, as riders leave their Manhattan offices to head back to their Brooklyn homes.

We can observe this phenomenon directly from the data, by looking at an hourly graph of trips that travel between Manhattan and the outer boroughs:

Sure enough, in the mornings there are more rides from Brooklyn to Manhattan than vice versa, while in the evenings there are more people riding from Manhattan to Brooklyn. For what it’s worth, most Citi Bike trips start and end in Manhattan. The overall breakdown since the program’s expansion in August 2015:

- 88% of trips start and end in Manhattan

- 8% of trips start and end in an outer borough

- 4% of trips travel between Manhattan and an outer borough

There are other distinct commuting patterns in the animation: the stretch of 1st Avenue heading north from 59th Street has very little Citi Bike traffic in the morning, but starting around 5 PM the volume picks up as people presumably head home from their Midtown offices to the Upper East Side.

Similarly, if we look during the morning rush at the parallel stretches of 1st and 2nd avenues stretching from the Lower East Side through Murray Hill, there’s clearly more volume heading north along 1st Avenue heading into Midtown. In the evening there’s more volume heading south along 2nd Avenue, as workers head home to the residential neighborhoods.

If we take all trips since Citi Bike’s expansion in August 2015, and again assume everyone followed Google Maps cycling directions, we can see which road segments throughout the city are most traveled by Citi Bikes. Here’s a map showing the most popular roads, where the thickness and brightness of the lines are based on the number of Citi Bikes that traveled that segment (click here to view higher resolution):

This map is reminiscent of the maps of taxi pickups and drop offs from my previous post, but they’re actually a bit different. The taxi maps were made of individual dots, where each dot was a pickup or drop off, while the Citi Bike map above counts each trip as a series of line segments, from the trip’s starting point to its finish.

The map shows a handful of primary routes for cyclists: 8th and 9th avenues heading uptown and downtown, respectively, on the west side, and 1st and 2nd avenues heading uptown and downtown, respectively, on the east side. The single road segment most trafficked by Citi Bikes lies along 8th Avenue, from W 28th Street to W 29th Street. Other main bike routes include Broadway, cutting diagonally across Midtown Manhattan, and the west side bike path along the Hudson River.

Remember that the map and animation assume people follow Google Maps cycling directions, which is definitely not always true. Google Maps seems to express strong preference for roads that have protected bike paths, which is why, for example, 8th Avenue has lots of traffic heading uptown, but 6th Avenue has very little. Both avenues head northbound, but only 8th Avenue has a protected bike path.

The Data

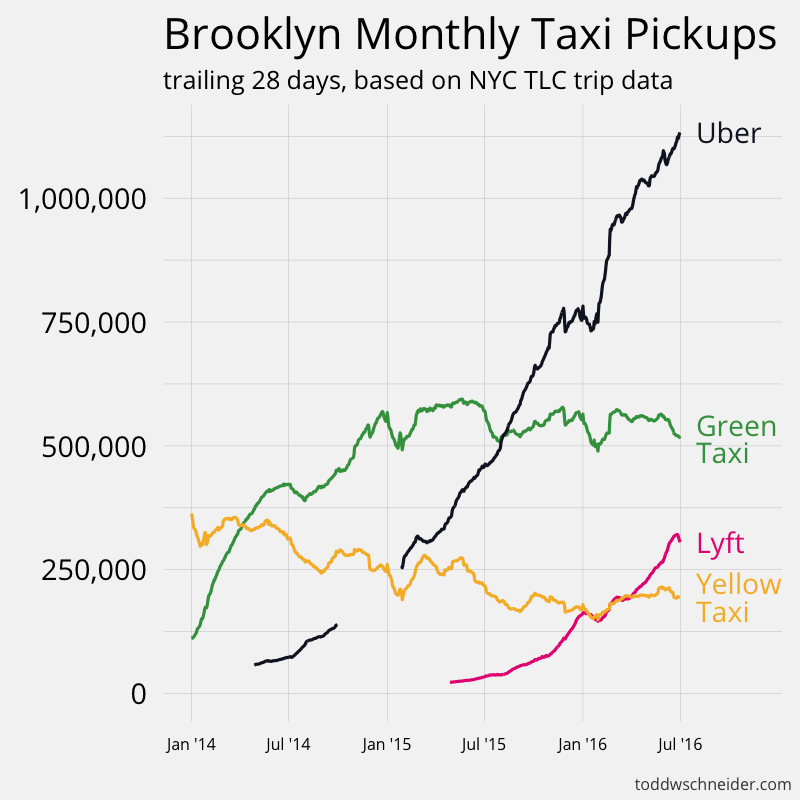

Unlike taxis, Citi Bikes cannot pick up and drop off at any arbitrary point in the city. Instead, riders can pick up and drop off bikes at finite number of stations across the city. Citi Bikes haven’t reached the ubiquity of taxis—in 2015 there were likely about 175 million taxi trips, 35 million Uber trips, and 10 million Citi Bike rides—but the bike share has plans to continue its expansion in the coming years.

Citi Bike makes data available for every individual trip in the system. Each trip record includes:

- Station locations for where the ride started and ended

- Timestamps for when the ride started and ended

- Rider gender

- Rider birth year

- Whether the rider is an annual Citi Bike subscriber or a short-term customer

- A unique identifier for the bike used

Here’s a graph of monthly usage since the program’s inception in June 2013:

Not surprisingly, there are dramatically fewer Citi Bike rides during the cold winter months. We’ll attempt to quantify the weather’s impact on Citi Bike ridership later in this post. The August 2015 increase in rides corresponds to the system’s first major expansion, which added nearly 2,000 bikes and 150 stations across Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan.

The system gets more usage on weekdays than on weekends, and if we look at trips by hour of the day, we can see that weekday riders primarily use Citi Bikes to commute to and from work, with peak hours from 8–9 AM and 5–7 PM. Weekend riders, on the other hand, prefer a more leisurely schedule, with most weekend rides occurring in the mid afternoon hours:

Age, Gender, and the Accuracy of Google Maps Cycling Time Estimates

The age and gender demographic data can be combined with Google Maps cycling directions to address a host of interesting questions, including:

- How fast do Citi Bike riders tend to travel?

- How accurate are Google Maps cycling time estimates?

- How do age and gender impact biking speed?

For each trip, we’ll proxy the trip’s average speed by taking the distance traveled according to Google Maps, and dividing by the amount of time the trip took. This probably understates the rider’s actual average bike speed, since the trip includes time spent unlocking the bike from the origin station, adjusting it, perhaps checking a phone for directions or dealing with other distractions, and returning the bike at the destination station.

Additionally, it assumes the rider follows Google Maps directions. If the rider actually took a longer route than the one suggested by Google, that would be more distance traveled, and we would underestimate the average trip speed. On the other hand, if the rider took a more direct route than suggested by Google, it’s possible we might overestimate the trip speed.

We have no idea about any individual rider’s intent: some riders are probably trying to get from point A to point B as quickly as safely possible, while others might want to take a scenic route which happens to start at point A and end at point B. The latter group will almost certainly not follow a direct route, and so we’ll end up calculating a very slow average speed for these trips, even if the riders were pedaling hard the entire time.

Accordingly, for an analysis of bike speed, I restricted to the following subset of trips, which I at least weakly claim is more likely to include riders who are trying to get from point A to point B quickly:

- Weekdays, excluding holidays

- Rush hour (7–10 AM, 5–8 PM)

- Annual subscribers

- Average trip speed between 4 and 35 miles per hour (to avoid faulty data)

I then bucketed into cohorts defined by age, gender, and distance traveled, and calculated average trip speeds:

The average speed across all such trips is 8.3 miles per hour, and the graph makes clear that younger riders tend to travel faster than older riders, men tend to travel faster than women, and trips covering longer distances have higher average speeds than shorter distance trips.

It’s also interesting to compare actual trip times to estimated times from Google Maps. Google Maps knows, for example, that the average speed along a wide, protected bike path will be faster than the speed along a narrow cross street that has no dedicated bike lane. I took the same cohorts and calculated the average difference between actual travel time and Google Maps estimated travel time:

If everyone took exactly the amount of time estimated by Google Maps cycling directions, we’d see a series of flat lines at 0. However, every bucket has a positive difference, meaning that actual trip times are slower than predicted by Google Maps, by an average of 92 seconds. As mentioned earlier, part of that is because Google Maps estimates don’t account for time spent transacting at Citi Bike stations, and we can’t guarantee that every rider in our dataset was even trying to get from point A to B quickly.

I ran a linear regression in R to model the difference between actual and estimated travel time as a function of gender, age, and distance traveled. The point of the regression isn’t so much to make any accurate predictions—it’d be especially bad to extrapolate the regression for longer distance trips—but more to understand the relative magnitude of each variable’s impact:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

The regression’s low R^2 of 0.055 reiterates that the data has lots of variance, and for any given trip the model is unlikely to produce a particularly accurate estimate. But the model at least gives us a simple formula to make a crude estimate of how long a Citi Bike subscriber’s rush hour trip will take relative to the Google Maps estimate:

- Start with 34

- If male, subtract 87

- Add (2.2 * age in years)

- Add (25.7 * trip distance in miles)

The result is the average number of seconds between actual and Google Maps estimated trip times, with a positive number indicating a slower than estimated trip, and a negative number indicating a faster than estimated trip. Yes, it means that for every year you get older, you’re liable to be 2.2 seconds slower on your regular Citi Bike commute route!

Anonymizing Data is Hard!

In my post about taxi data, I included a section about data privacy, noting that precise pick up and drop off coordinates might reveal potentially sensitive information about where people live, work, and socialize. Citi Bike data does not have the same issues with precise coordinates, since all Citi Bike trips have to start and end at one of the 493 fixed stations.

But unlike the taxi data, Citi Bike includes demographic information about its riders, namely gender, birth year, and subscriber status. At first glance that might not seem too revealing, but it turns out that it’s enough to uniquely identify many Citi Bike trips. If you know the following information about an individual Citi Bike trip:

- The rider is an annual subscriber

- Their gender

- Their birth year

- The station where they picked up a Citi Bike

- The date and time they picked up the bike, rounded to the nearest hour

Then you can uniquely identify that individual trip 84% of the time! That means you can find out where and when the rider dropped off the bike, which might be sensitive information. Because men account for 77% of all subscriber trips, it’s even easier to uniquely identify rides by women: if we restrict to female riders, then 92% of trips can be uniquely identified. It’s also easier to identify riders who are significantly younger or older than average:

If instead of knowing the trip’s starting time to the nearest hour you only knew it to the nearest day, then you’d be able to identify 28% of all trips, but still 49% of trips by women.

On some level this shouldn’t be too surprising: a famous paper by Latanya Sweeney showed that 87% of the U.S. population is uniquely identified by birthdate, gender, and ZIP code. We probably have a bias toward underestimating how easy it is to identify people from what seems like limited data, and I hope that people think about that when they decide what data should be made publicly available.

Magical Transports

Disclaimer: I know nothing about the logistics of running a bike share system. I’d imagine, though, that one of the big issues is making sure that there are bikes available at stations where people want to pick them up. If station A starts the day with lots of bikes, but people take them out to other stations and nobody returns any bikes to A, then A will run out of bikes, and that’s bad.

The bike share operator could transport additional bikes to A to meet demand, but that costs time/money, so the operator probably wants to avoid it as much as possible. The data lets us measure how often bikes “magically” transport from one station to another, even though no one took a ride. I took each bike drop off, and calculated the percentage of rides where the bike’s next trip started at a different station from where the previous trip dropped off:

From July 2013 through March 2015, around 13% of bikes were somehow transported from their drop off stations to different stations before being ridden again. Since April 2015, though, that rate has decreased to about 4%. I have no idea why: my first guess was that there were more total bikes added to the system, but the number of bikes in use did not change in March 2015. There were no stations added or removed around then either, so that seems like an unlikely explanation. Maybe the operator developed a smarter system to allocate bikes, which resulted in a lower transfer percentage?

Different neighborhoods have different transfer patterns, too. Bikes dropped off in Manhattan’s East Village have a much higher chance of being transported if they’re dropped off in the evening:

While transfers are more likely in Fort Greene, Brooklyn for bikes dropped off in the morning:

And in Midtown, Manhattan, drop offs at morning or evening rush hour are more likely to be transported:

Add it all up and I’m not exactly sure what it means, but it seems like something that could be pursued further. The Citi Bike program has plans to continue its expansion in 2016, I wonder how the new stations will impact the transport rate?

Quantifying the Impact of the Weather on Citi Bike Activity

We saw earlier that there are many more Citi Bike rides in the summer than in the winter. It’s not surprising: anyone with a modicum of common sense knows that it’s not very pleasant to bike when it’s freezing cold. Similarly, biking is probably less popular on rainy and snowy days. This got me wondering: how well is Citi Bike’s daily ridership predicted by the weather?

I downloaded daily Central Park weather data from the National Climatic Data Center and joined it to the Citi Bike data in an effort to model the relationship between Citi Bike usage and the weather. The weather data includes a few variables, most notably:

- Daily max temperature

- Daily precipitation

- Daily snow depth

Even before I began investigating the data, I suspected that a linear regression would not be appropriate for the weather model, for two main reasons:

- Our dependent variable, total number of trips per day, is by definition positive. A standard linear regression can’t be guaranteed to produce a positive number

- The relationship between bike rides and the weather is probably nonlinear. For example, I’d guess the change in ridership between 40 degree and 60 degree days is probably a larger magnitude than the change in ridership between 60 degree and 80 degree days

We could use a linear model with log transformations to deal with problem 1, but even then we’d be stuck with the nonlinearity issue. Let’s confirm though that the relationship between weather and ridership is in fact nonlinear:

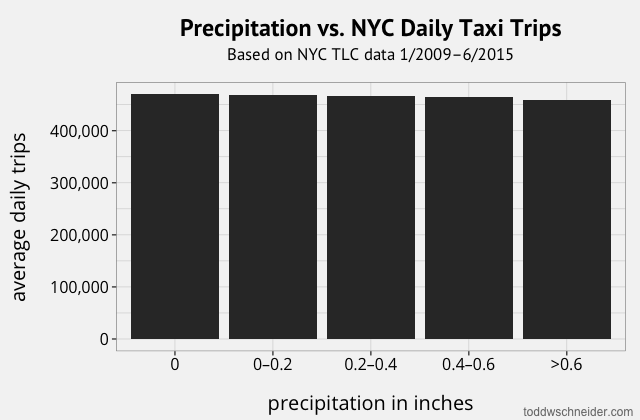

This graph makes it pretty clear that there’s a nonlinear relationship between rides and max daily temperature. The number of trips ramps up quickly between 30 and 60 degrees, but above 60 degrees or so there’s a much weaker relationship between ridership and temperature. Let’s look at rainy days:

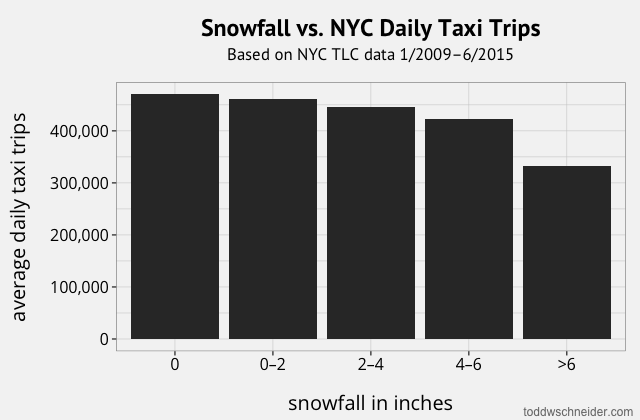

And snowy days:

Rain and snow are, not surprisingly, both correlated with lower ridership. The linearity of the relationships is less clear—there are also fewer observations in the dataset compared to “normal” days—but intuitively I have to believe that there’s a diminishing marginal effect of both, i.e. the difference between no rain and 0.1 inches of rain is more significant than the difference between 0.5 and 0.6 inches.

To calibrate the model, instead of using R’s lm() function, we’ll use the nlsLM() function from the minpack.lm package, which implements the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm to minimize squared error for a nonlinear model.

For the nonlinear regression, we first need to specify the form of the model, which I chose to look like this:

The d variables are known values for a given date d, β variables are calibrated parameters, and the capitalized functions are intermediaries that are strictly speaking unnecessary, i.e. we could write the whole model on a single line, but I find the intermediate functions make things easier to reason about. Let’s step through the model specification, one line at a time:

-

dtrips is the number of Citi Bike trips on date d, the dependent variable in our model. We’re breaking trips into two components: a baseline component, which is a function of the date, and a weather component, which is a function of the weather on that date.

-

The Baseline(d) function uses an exponent, which guarantees that it will produce a positive output. It has 3 calibrated parameters: a constant, an adjustment for days that are non-holiday weekdays, and a fudge factor for dates in the “post-expansion era”, defined as after August 25, 2015, when Citi Bike added nearly 150 stations to the system.

-

The Weather(d) function uses every mortgage prepayment modeler’s favorite formula: the s-curve. I readily admit I have no “deep” reason for picking this functional form, but s-curves often behave well in nonlinear models, and the earlier temperature graph kind of looked like an s-curve might fit it well.

-

The input to the s-curve, WeatherFactor(d), is a linear combination of the maximum temperature, precipitation, and snow depth on date d.

The input data is available here as a csv, and you can see the exact R commands, output, and parameter values here, but the short version is that the model calibrates to what seem like reasonable parameters. Assuming we hold all other variables constant, the model predicts:

- Raising the daily max temperature from 40 to 60 degrees increases ridership by 12,100 trips, while raising the temperature from 60 to 80 degrees increases ridership by 7,850 trips:

- 1 inch of rain has the same effect as decreasing the temperature by 24 degrees

- 1 inch of snow on the ground has the same effect as decreasing the temperature by 1.4 degrees.

In order to assess the model’s goodness of fit, we’ll look at some more graphs, starting with a scatterplot of actual vs. predicted values. Each dot represents a single day in the dataset, where the x-axis is the actual number of trips on that day, and the y-axis is the model-predicted number of trips:

The model’s root-mean-square error is 4,138, and residuals appear to be at least roughly normally distributed. Residuals appear to exhibit some heteroscedasticity, though, as the residuals have lower variance on dates with fewer trips.

The effect of the “post-expansion” fudge factor is evident in the top-right corner of the scatterplot, where it looks like there’s an asymptote around 36,000 predicted trips for dates before August 26, 2015. Ideally we’d formulate the model to avoid using a fudge factor—maybe by modeling trips at the individual station level, then aggregating up—but we’ll conveniently gloss over that.

We can also look at the time series of actual vs. predicted, aggregating to monthly totals in order to reduce noise:

I make no claim that it’s a perfect model—it uses imperfect data, has some smelly features and omissions, and all of the usual correlation/causation caveats apply—but it seems to do at least an okay job quantifying the impact of temperature, rain, and snow on Citi Bike ridership.

In Conclusion

As always, there are still plenty more things we could study in the dataset. Bad weather probably affects cycling speeds, so we could take that into account when measuring speeds and Google Maps time estimates.

Ben Wellington at I Quant NY did some demographic analysis by station, it might be interesting to see how that has evolved over time.

I wonder about modeling ridership at the individual station level, especially as stations are added in the future. Adding a new station is liable to affect ridership at existing stations—and it’s not even clear whether positively or negatively. A new station might cannibalize trips from other nearby stations, which wouldn’t increase total ridership by very much. But it’s also possible that a new station could have a synergistic effect with an existing station: imagine a scenario where a neighborhood with bad subway access gets a Citi Bike station, then an existing station located near the closest subway might see a surge in usage.

There are also probably plenty of analyses that could be done comparing Citi Bike data with the taxi and Uber data: what neighborhoods have the highest and lowest ratios of Citi Bike rides compared to taxi trips? And are there any commutes where it’s faster to take a Citi Bike than a taxi during rush hour traffic? Alas, these will have to wait for another time…

GitHub

There are scripts to download, process, and analyze the data in the nyc-citibike-data repository. A csv of the raw data for the weather analysis (daily trip totals plus weather data) is included in the repo, in case you don’t want to download all of the data.