The Simpsons needs no introduction. At 27 seasons and counting, it’s the longest-running scripted series in the history of American primetime television.

The show’s longevity, and the fact that it’s animated, provides a vast and relatively unchanging universe of characters to study. It’s easier for an animated show to scale to hundreds of recurring characters; without live-action actors to grow old or move on to other projects, the denizens of Springfield remain mostly unchanged from year to year.

As a fan of the show, I present a few short analyses about Springfield, from the show’s dialogue to its TV ratings. All code used for this post is available on GitHub.

The Simpsons characters who have spoken the most words

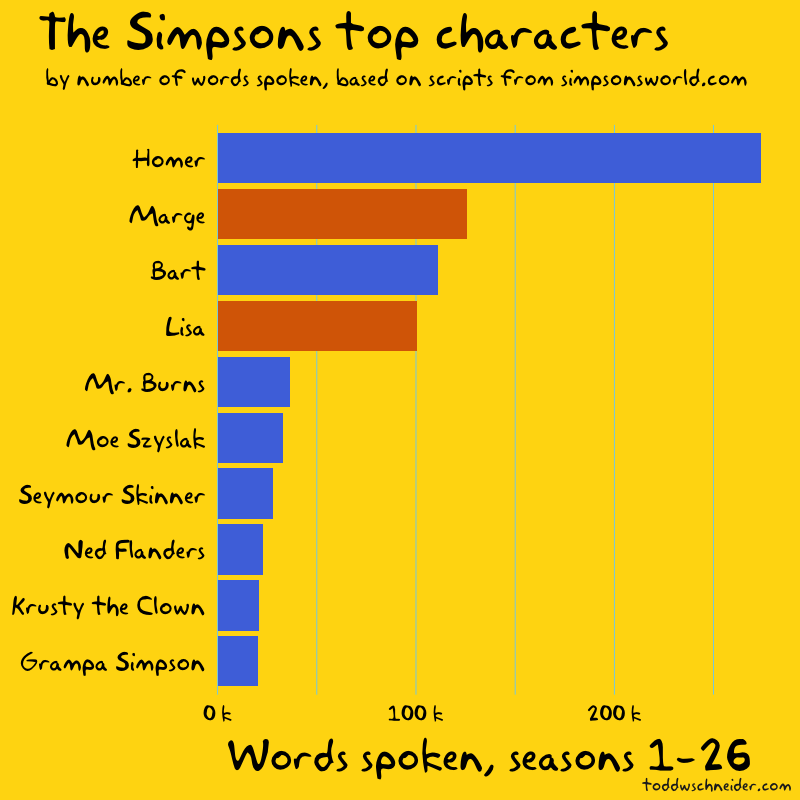

Simpsons World provides a delightful trove of content for fans. In addition to streaming every episode, the site includes episode guides, scripts, and audio commentary. I wrote code to parse the available episode scripts and attribute every word of dialogue to a character, then ranked the characters by number of words spoken in the history of the show.

The top four are, not surprisingly, the Simpson nuclear family.

If you want to quiz yourself, pause here and try to name the next 5 biggest characters in order before looking at the answers…

Of course Homer ranks first: he’s the undisputed most iconic character, and he accounts for 21% of the show’s 1.3 million words spoken through season 26. Marge, Bart, and Lisa—in that order—combine for another 26%, giving the Simpson family a 47% share of the show’s dialogue.

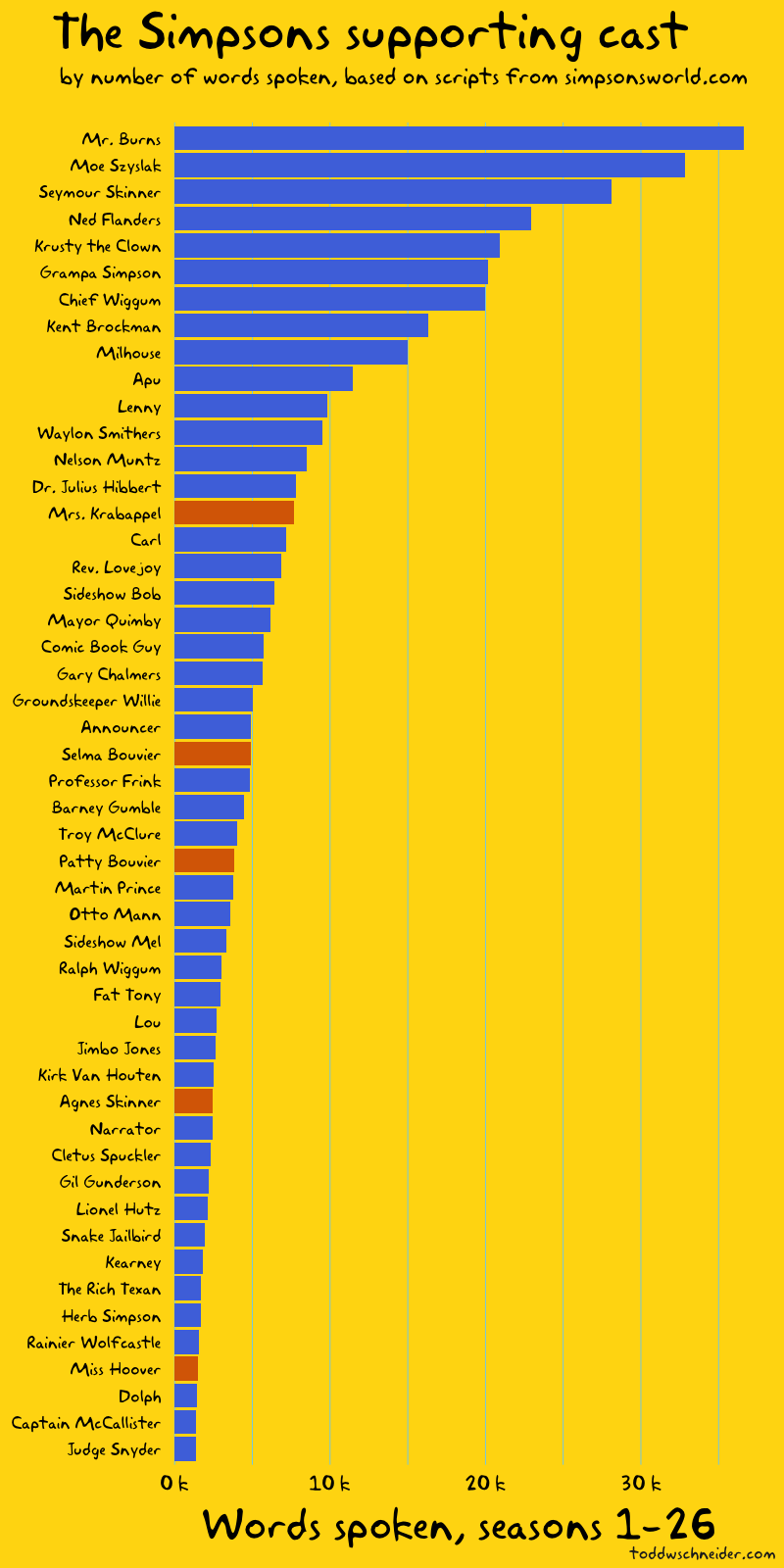

If we exclude the Simpson nuclear family and focus on the top 50 supporting characters, the results become a bit less predictable, if not exactly surprising.

Mr. Burns speaks the most words among supporting cast members, followed by Moe, Principal Skinner, Ned Flanders, and Krusty rounding out the top 5.

Gender imbalance on The Simpsons

The colors of the bars in the above graphs represent gender: blue for male characters, red for female. If we look at the supporting cast, the 14 most prominent characters are all male before we get to the first woman, Mrs. Krabappel, and only 5 of the top 50 supporting cast members are women.

Women account for 25% of the dialogue on The Simpsons, including Marge and Lisa, two of the show’s main characters. If we remove the Simpson nuclear family, things look even more lopsided: women account for less than 10% of the supporting cast’s dialogue.

A look at the show’s list of writers reveals that 9 of the top 10 writers are male. I did not collect data on which writers wrote which episodes, but it would make for an interesting follow-up to see if the episodes written by women have a more equal distribution of dialogue between male and female characters.

Eye on Springfield

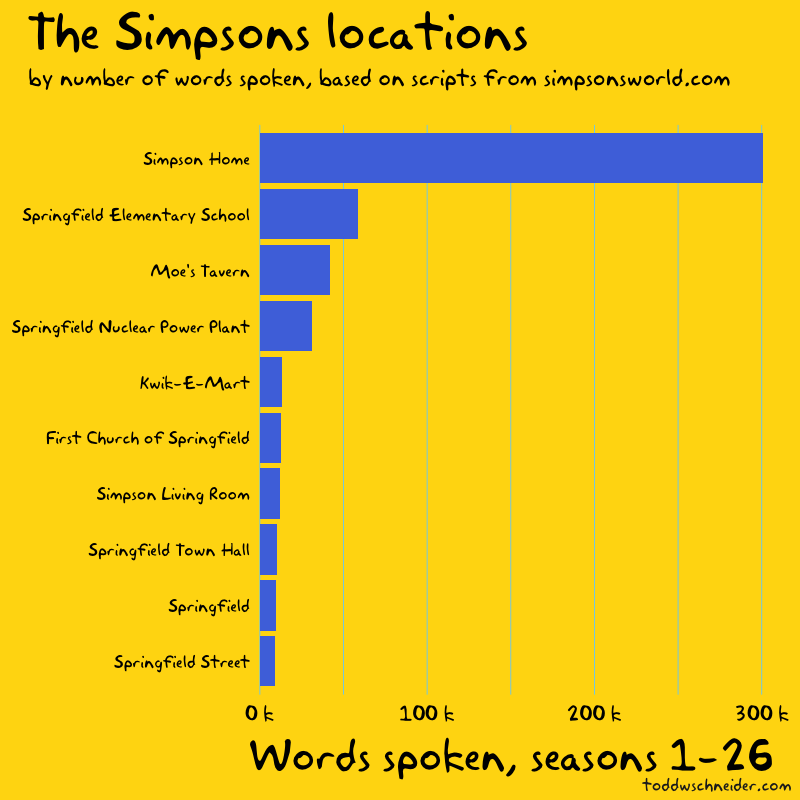

The scripts also include each scene’s setting, which I used to compute the locations with the most dialogue.

The location data is a bit messy to work with—should “Simpson Living Room” really be treated differently than “Simpson Home”—but nevertheless it paints a picture of where people spend time in Springfield: at home, school, work, and the local bar.

The Bart-to-Homer transition?

Per Wikipedia:

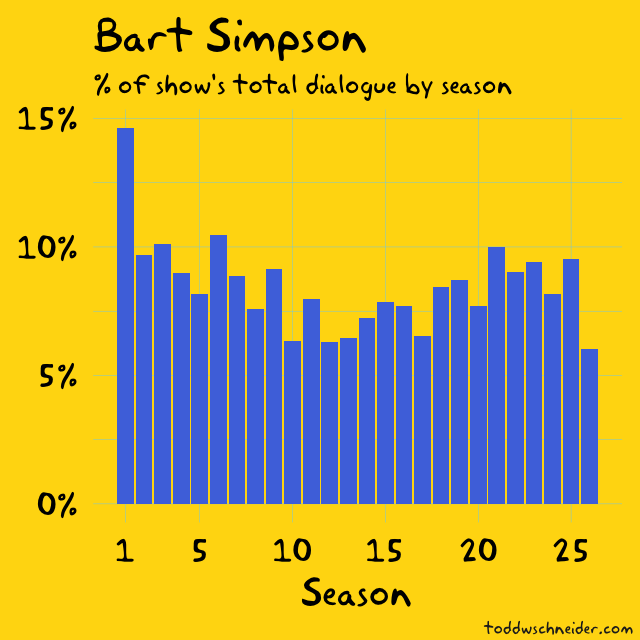

While later seasons would focus on Homer, Bart was the lead character in most of the first three seasons

I’ve heard this argument before, that the show was originally about Bart before switching its focus to Homer, but the actual scripts only seem to partially support it.

Bart accounted for a significantly larger share of the show’s dialogue in season 1 than in any future season, but Homer’s share has always been higher than Bart’s. Dialogue share might not tell the whole story about a character’s prominence, but the fact is that Homer has always been the most talkative character on the show.

The Simpsons TV ratings are in decline

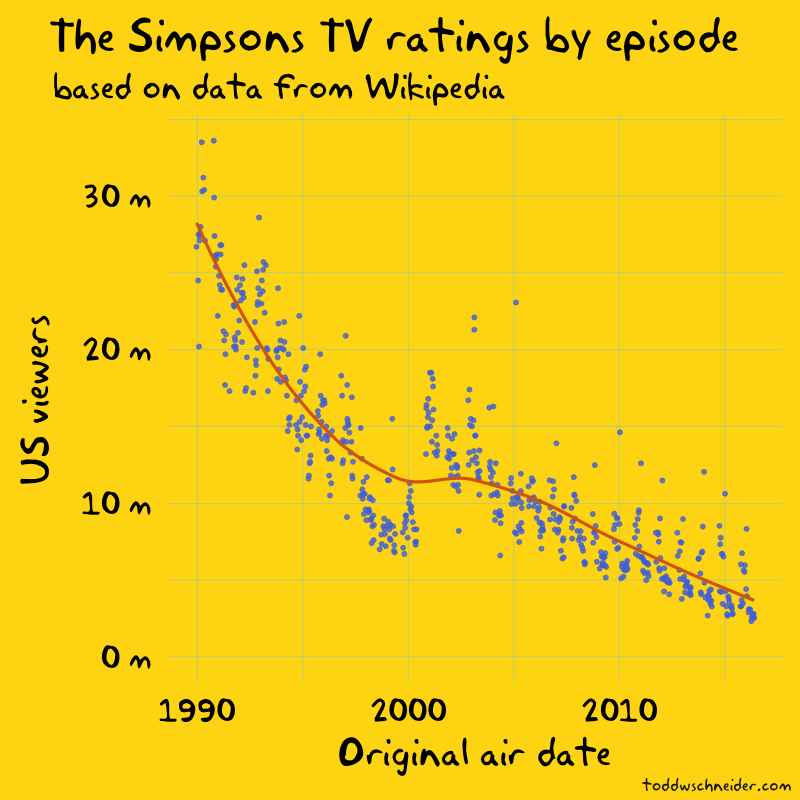

Historical Nielsen ratings data is hard to come by, so I relied on Wikipedia for Simpsons episode-level television viewership data.

Viewership appears to jump in 2000, between seasons 11 and 12, but closer inspection reveals that’s when the Wikipedia data switches from reporting households to individuals. I don’t know the reason for the switch—it might have something to do with Nielsen’s measurement or reporting—but without any other data sources it’s difficult to confirm.

Aside from that bump, which is most likely a data artifact, not a real trend, it’s clear that the show’s ratings are trending lower. The early seasons averaged over 20 million viewers per episode, including Bart Gets an “F”, the first episode of season 2, which is still the most-watched episode in the show’s history with an estimated 33.6 million viewers. The more recent seasons have averaged less than 5 million viewers per episode, more than an 80% decline since the show’s beginnings.

TV ratings have declined everywhere, not just on The Simpsons

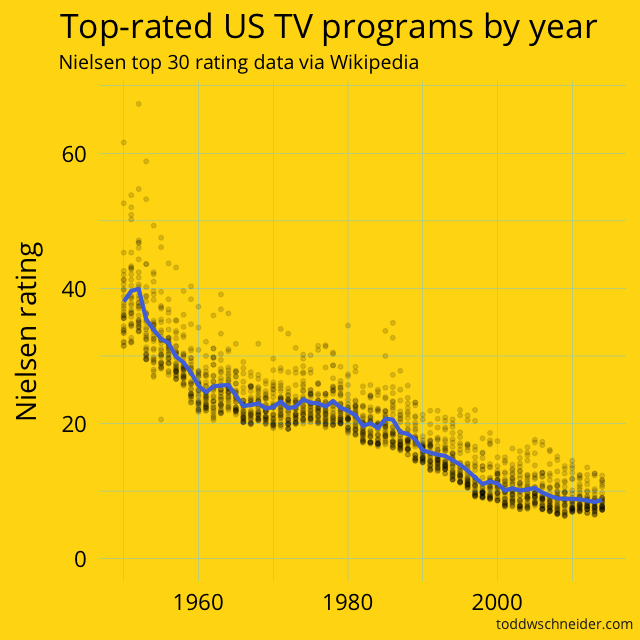

Although the ratings data looks bad for The Simpsons, it doesn’t tell the whole story: TV ratings for individual shows have been broadly declining for over 60 years.

When The Simpsons came out in 1989, the highest 30 rated shows on TV averaged a 17.7 Nielsen rating, meaning that 17.7% of television-equipped households tuned in to the average top 30 show. In 2014–15, the highest 30 rated shows managed an 8.7 average rating, a decline of 50% over that 25 year span.

If we go all the way back to the 1951, the top 30 shows averaged a 38.2 rating, which is more than triple the single highest-rated program of 2014–15 (NBC’s Sunday Night Football, which averaged a 12.3 rating).

Full data for the top 30 shows by season is available here on GitHub

I have no proof for the cause of this decline in the average Nielsen rating of a top 30 show, but intuitively it must be related to the proliferation of channels. TV viewers in the 1950s had a small handful of channels to choose from, while modern viewers have hundreds if not thousands of choices, not to mention streaming options, which present their own ratings measurement challenges.

We could normalize Simpsons episode ratings by the declining top 30 curve to adjust for the fact that it’s more difficult for any one show to capture as large a share of the TV audience over time. But as mentioned earlier, the normalization would only account for about a 50% decline in ratings since 1989, while The Simpsons ratings have declined more like 80-85% over that horizon.

Alas, I must confess, I stopped watching the show around season 12, and Simpsons World’s episode view counts suggest that modern streaming viewers are more interested in the early seasons too, so it could just be that people are losing interest.

As I write this, The Simpsons is under contract to be produced for one more season, though it’s entirely possible it will be renewed. But ultimately Troy McClure said it best at the conclusion of the The Simpsons 138th Episode Spectacular, which, it’s hard to believe, now covers less than 25% of the show’s history:

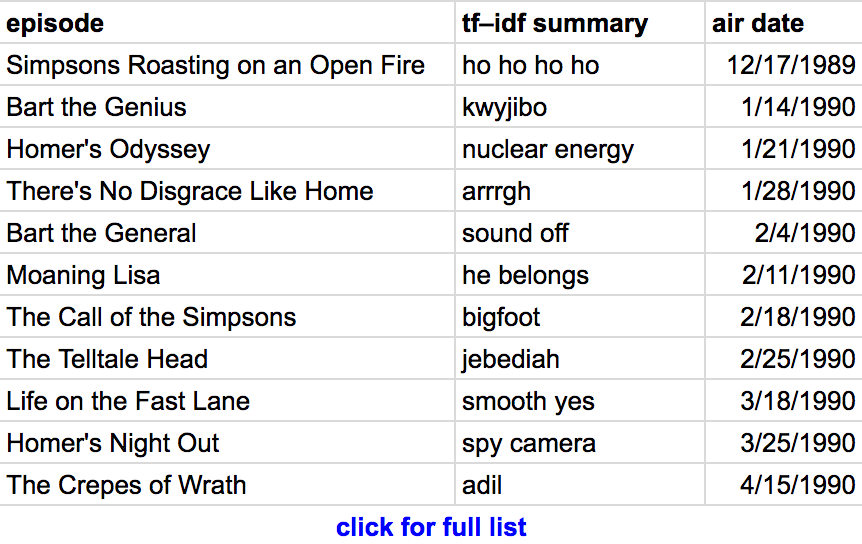

Automated episode summaries using tf–idf

Term frequency–inverse document frequency is a popular technique used to determine which words are most significant to a document that is itself part of a larger corpus. In our case, the documents are individual episode scripts, and the corpus is the collection of all scripts.

The idea behind tf–idf is to find words or phrases that occur frequently within a single document, but rarely within the overall corpus. To use a specific example from The Simpsons, the phrase “dental plan” appears 19 times in Last Exit to Springfield, but only once throughout the rest of the show, and sure enough the tf–idf algorithm identifies “dental plan” as the most relevant phrase from that episode.

I used R’s tidytext package to pull out the single word or phrase with the highest tf–idf rank for each episode; here’s the relevant section of code.

The results are pretty good, and should be at least slightly entertaining to fans of the show. Beyond “dental plan”, there are fan-favorites including “kwyjibo”, “down the well”, “monorail”, “I didn’t do it”, and “Dr. Zaius”, though to be fair, there are also some less iconic results.

You can see the full list of episodes and “most relevant phrases” here.

Another interesting follow-up could be to use more sophisticated techniques to write more complete episode summaries based on the scripts, but I was pleasantly surprised by the relevance of the comparatively simple tf–idf approach.

Code on GitHub

All code used in this post is available on GitHub, and the screencaps come from the amazing Frinkiac